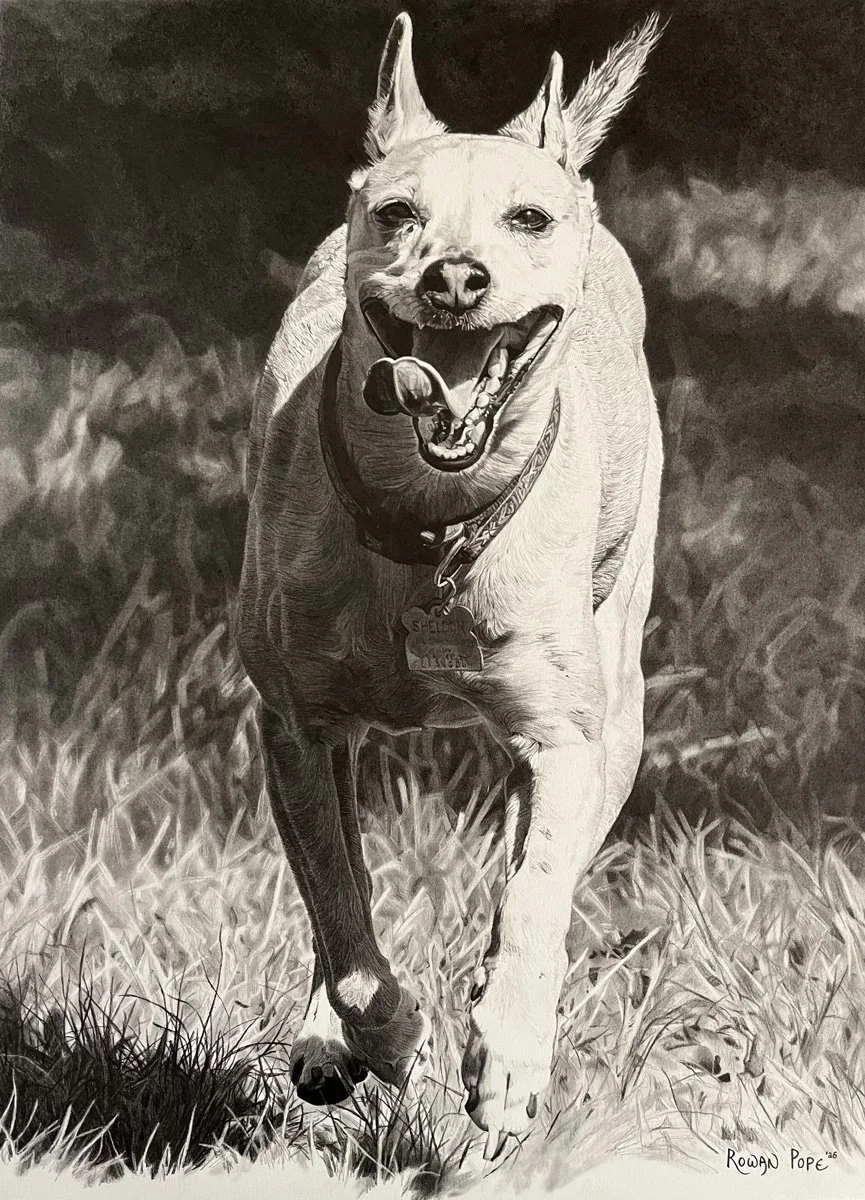

NATURE, ANIMALS, and LANDSCAPES

Artists like Durer and Rodin focused on the mundane and the inherent beauty in simple, everyday objects and places – elevating them to the condition of fine art. They portrayed the “ugly” as beautiful, and the “unconventional” as splendorous and unique. Real-life was not mannerist or perfect, it had a grittier, glittering, tangible, sensual soul. The feathers of a bird’s wing, the intricacy of a dull patch of ground, the crumpled body of an old woman, and the wrinkled face of an old man with a broken nose – all became subjects of worship and revelation. Bosschaert and de Heem presented simple, ordinary flowers as a subject that contained a deeper meaning, as a lavish, elaborate dream. Ghirlandaio presented the warty nose of an old man not as an object of repulsion or disgust, but as a natural curiosity, a marvel. Wyeth observed simple nature not as plain, but as a uniquely integrated spectacle. This artistic mode – presenting the mundane as miraculous – is fundamentally paradoxical and forces the viewer to question and to reexamine their surrounding world and their everyday lives.

Photorealists continued this paradoxical tradition with its signature visual literalism and conceptual irony by concentrating on commonplace subjects and characterizing them as extraordinary and unexpected. Their goal, much like Pop art, was the legitimization of commercial and everyday objects as high-art subject matter – to make the ordinary and the routine become monumental, sublime, and larger than life.

In our drawings, each wrinkle on a person’s face, each curled, dessicated leaf is precious, like the moments of our lives, belonging exactly where it is, stirring and indispensable and unexpected.